Information Controls during Military Operations: The case of Yemen during the 2015 political and armed conflict

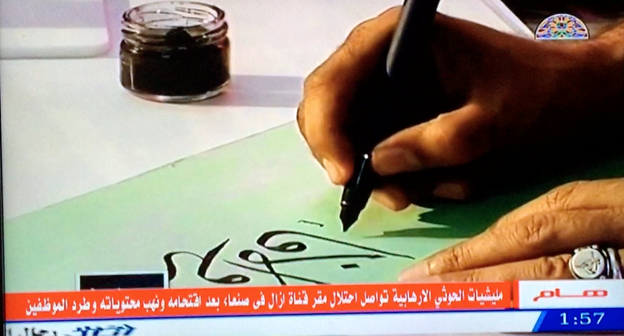

Screenshot from Yemeni private TV channel Azaal TV. Arabic banner says: “The terrorist Houthi militia continues to occupy Azaal TV station headquarters in Sana’a after it raided it, confiscated its equipment, and expelled its staff.” Image credit: Naser Noor

Screenshot from Yemeni private TV channel Azaal TV. Arabic banner says: “The terrorist Houthi militia continues to occupy Azaal TV station headquarters in Sana’a after it raided it, confiscated its equipment, and expelled its staff.” Image credit: Naser Noor

Key Findings

- This report provides a detailed, mixed methods analysis of Information controls related to the Yemen armed conflict, with research commencing at the end of 2014 and continuing through October 20, 2015.

- The research confirms that Internet filtering products sold by the Canadian company Netsweeper have been installed on and are presently in operation in the state-owned and operated ISP YemenNet, the most utilized ISP in the country.

- Netsweeper products are being used to filter critical political content, independent media websites, and all URLs belonging to the Israeli (.il) top-level domain.

- These new categories of censorship are being implemented by YemenNet, which is presently under the control of the Houthis (an armed rebel group, certain leaders and allies of which are targeted by United Nations Security Council sanctions).

- We identify disruptions to infrastructure, such as electricity and fuel, as an important component of information controls in the conflict. Although we are unable to attribute specific disruptions to parties responsible, we find that on balance the limited access to information brought about by the disruptions favours the interests of the Houthis.

- Network measurements tests undertaken in Saudi Arabia and Iran show that there is a significant international “spillover” of information controls among state parties to the conflict; both states have blocked websites related to their opponents in the ongoing political and military conflicts.

Summary

Recent political conflicts and periods of violent unrest — such as those in Syria, Thailand, and Iraq — have demonstrated the ways in which information and communications often become a focal point of contestation during a crisis. As information becomes a critical factor in a conflict, information controls — which we define as actions conducted in or through information and communication technologies that seek to deny, disrupt, secure, or monitor information for political ends — may increase in scope, intensity, and depth. Authorities may introduce new types of censorship as a means of preventing information from leaving the country, or in some cases even cut off access to communications entirely, such as the Internet or mobile phones services. Service providers may be required to undertake emergency measures to control information or communications, or suspend services because of violence, loss of personnel, or disruptions to their infrastructure. Contests over information controls can also become “internationalized” as outside parties to the conflict, including neighboring states, companies, non-state groups, and civil society, get involved and take action that impacts the information environment in the zone of conflict and beyond.

This report presents research on information controls in the context of the ongoing Yemeni armed conflict. After months of crisis following the September 2014 Houthi rebel takeover of the capital Sana’a, the situation in Yemen degenerated into ongoing violent conflict. The conflict has expanded since 2014 to include a military response from a coalition of Arab states led by neighbouring Saudi Arabia.

Using a combination of network measurement tests, reference to technical data sources, as well as contextual and in-country field research, we undertook a detailed examination of information controls related to the Yemeni armed conflict from the end of 2014 to October 2015. Our research was guided by the following framing questions:

- How is access to infrastructure, including basic electricity and fuel, a component of information control in Yemen’s armed conflict? Do disruptions to infrastructure favour one side of the conflict over others? Can we attribute disruptions to infrastructure to specific parties to the armed conflict?

Citizens’ ability to access information has been significantly impacted by the ongoing violence, with deliberate power outages and shortages of fuel used to power generators further weakening the country’s infrastructure. Citizens are unable to power their computers, TVs, or mobile phones. These disruptions have limited citizens’ ability to communicate with their families, keep abreast of news related to local developments, or receive advance warning from Saudi-led coalition forces to leave their homes prior to airstrikes in active military conflict zones. The disruptions, though difficult to attribute to any particular group, favour the Houthis who have a demonstrated interest in restricting information flow.

- What other techniques of information control factor into the Yemen armed conflict?

Information controls in Yemen have taken different forms. The Houthi rebels have banned domestic telecommunication providers from sending news updates generated by local and regional media to subscribers. They have raided and shut down TV channels and radio stations, arrested journalists, raided newspaper offices, and blocked websites of local and regional media. We also take note of numerous reports of digital surveillance, but were unable to draw positive conclusions about the veracity of these reports or map Yemen’s surveillance infrastructure.

- Is Internet censorship a factor in the armed conflict? Have Yemen’s Internet content filtering practices shifted substantially, and if so how? How transparent is the filtering?

We find that information controls implemented by Yemen’s national ISP, YemenNet, a state-owned and operated national ISP that has served the entire country since 2001, and which is now controlled by the Houthi rebels, have changed substantially since the Houthi takeover of the capital and, by extension, control over the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology. Content filtering now includes a wide variety of political content, and blocking of the entire .il (Israel) domain. We also determine that all political filtering that targets local and regional news and media content is undertaken in a non-transparent way, with fake network error pages delivered back to users instead of block pages.

- What equipment is used for content filtering? Can we identify the manufacturer of filtering services? Did that company undertake any due diligence around providing services to a country in the midst of an armed conflict, and to ISPs now under the control of a group (the Houthis) whose leaders are subject to UN Security Council sanctions?

Our prior research on Yemen (as part of the OpenNet Initiative) identified Websense, and later Netsweeper, as commercial providers of content filtering services and equipment to Yemen’s ISPs. In our latest research, we are able to positively verify that Netsweeper is still provisioning services to YemenNet. We also conducted an experiment confirming that Netsweeper is actively updating Netsweeper installations in the country, and thus knows or has reason to know of the recent expansion of the filtering regime to include political content linked to the conflict and the Houthi takeover. As part of the research for this report, on October 9, 2015 we sent a letter to Netsweeper regarding its provision of services to YemenNet and its human rights due diligence. As of the date of publication, we have not received a reply.

- Have information controls been “internationalized” as part of the Yemen armed conflict?

In prior research, we have observed that information controls can “spill out” of a particular conflict and affect access to the Internet in other countries. To continue this line of inquiry, we undertook network measurements in Saudi Arabia and Iran. We find that that Saudi Arabia has implemented new Internet content filtering aligned with its military operations in Yemen. We also find that there is significant similarities between content filtering undertaken in Iran and that which has been implemented in Yemen since the Houthi takeover.

Our report begins with background to Yemen and the armed conflict, as well as to the history of information controls in the country. Part 1 provides a summary examination of information controls around the armed conflict based on contextual and field research. Part 2 presents the findings of the network measurement tests we undertook for Internet content filtering in Yemen, Saudi Arabia, and Iran, and details experiments we undertook to confirm Netsweeper’s provision of services in Yemen. We evaluate Netsweeper’s provision of services on the basis of existing human rights laws and norms, and provide details on questions we sent to the company. We conclude the report with observations on research on information controls in armed conflict in general, and the Yemen case in particular.